After a year-long hiatus, TJI is proud to announce the return of our Middle Grounds column, dedicated to capturing viewpoint diversity on a variety of topics.

This past semester was the first in which all first-year students were required to participate in the Engagements Pathway curriculum. It is described on UVA’s website as “The highlight of the General Education Curriculum. They comprise a yearlong sequence of courses that celebrate learning while introducing first-year students to the liberal arts and sciences.”

The consensus among students is mixed, with some favoring its emphasis on academic exploration, and others feeling contained by taking courses of which they have no interest. Hear both sides of the story from two of our TJI staffers and decide for yourself; do Engagements help or hurt UVA’s gen-ed curriculum?

- The Editorial Board

Pro: The Engagements Foster Intellectual Curiosity and aren’t Burdensome

The University of Virginia values, above a great number of other matters of relative importance, the substance inherent to a liberal arts education. Not only does this necessitate, for this University in particular, a broad catalog of knowledge to be available at the institution, but it also unequivocally asserts the intention for students in the college to engage with a vast array of knowledge. The primary verb here—to engage—is precisely what motivates the Engagements track at UVA, which students are expected to undergo, with few exceptions. For the majority of students in the college, their first year will comprise two Engagements courses per semester, each spanning a seven-week period. The Engagements have topics in four primary categories—Engaging Aesthetics, Empirical and Scientific Engagement, Engaging Differences, and Ethical Engagements—each of which entails an intensive and comprehensive exploration of a given topic. Most often, the Engagements are a means to the end of intellectually connecting with our first-year peers, and in addition, developing more complex ideas regarding the topic under consideration. Such is the epitome of curiosity and truth, of skepticism and argumentation, of cooperation and unity, all contained under an umbrella which is unafraid of inquiry and is predicated on cognitive engagement.

The hidden curriculum of many universities relays a standard of what designates a student as a functional member of society, coordinating graduation requirements as such. In this same way, the Engagements endorses branches of knowledge and characteristics that the college wishes to bestow upon each of its students—tenacity, creativity, introspection, perceptiveness, and our willingness to exchange firm opinions, among other things.

What is more, through this most essential medium, students can appreciate specific subjects that they may otherwise never encounter by their own volition. Take, for example, a biology major who plans to one day go to medical school—it would often be conceived that there is, then, no inherent value to studying philosophy or literature. However, this is intensely wrongful logic. Even for an individual who never has dreamt of becoming a scholar in such areas of study, there exists a purpose in substantiating the ability to communicate and to understand a wide array of perspectives, as well as manners of conveying these perspectives. In a medical sense, perhaps this would one day motivate, to an amplified degree, a student of medicine working to the best of their capability; perhaps the only way we can grasp what it means to be lively, and therefore what it would mean to save a life, is to engage with romance, and with superfluously contemplative writings, and with a dimension of beauty that the Engagements do not let us deny ourselves.

Regardless, many students of the college would argue that the Engagements pose unnecessary inconveniences to first-year students who are most likely adjusting to several other aspects of the college experience—they are too much work and far more trouble than they are worth. When precisely did students of this university begin to worry that their academic efforts are futile?

One gives themself to the content no more than the revelation of the arts offers itself to them, and this way no one is dissatisfied—yet this is challenged relentlessly. In actuality, each Engagement only appears, at a glance, like a surplus of work, but in most cases, the student has an honest choice whether they care to engage as the course recommends. The most fascinated student will go beyond the syllabus and the requirements, whereas the most disinterested student will casually complete discussion posts without having digested the material much at all. Each student is certainly capable of attaining an adequate grade in the course at the end of the quarter. Much of the Engagements track is tantamount to weighing its significance, which is largely ambiguous, and the grievance I am inclined to most openly express is that students would prefer to ignore this truth instead of recognizing that any one of us has the power to decide for ourselves the extent to which we wish to engage.

In any case, being thrust into surroundings of such niche curiosities is bound to introduce, at minimum, the notion that there is meaning in the exploration of intellectual curiosity, even just for the sake of doing so. At the conclusion of each Engagement, what remains is merely the truth of why each of us is here at this university, and we must come to terms with this dually substantial predisposition to engage or not to engage.

- Beckett Wilkinson

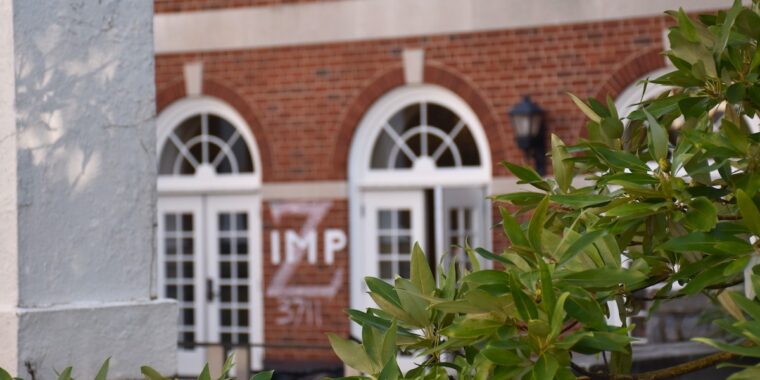

Con: The Engagements are Impractical and Constrain Academic Freedom

Touted as the “highlight of the General Education Curriculum,” the University of Virginia’s Engagements program consists of four mandatory classes taken by first-years in the College of Arts and Sciences, encompassing the pillars of aesthetics, difference, empiricism, and ethics. The intention behind the Engagements program is to encourage students to “ask big questions” through small, seminar-style classes, contributing to the University’s mission of providing a well-rounded liberal arts education. However, I simply see Engagements as part of the scam that are gen-ed requirements. I am not just some STEM major complaining about the humanities—I actually do enjoy some of the discussions in my Engagements classes. While I can appreciate the thought-provoking nature of these discussions, their practicality within the broader context of the U.S. higher education system is nonexistent.

Recently, the UVA Board of Visitors approved a 3% increase in undergraduate tuition for the 2024-25 academic year. In the College of Arts and Sciences, the estimated total yearly cost of attendance is $39,494 for in-state students, and $78,214 for out-of-state students. As nation-wide student debt continues to rise, graduating early seems like an attractive option, but UVA’s policies make this frustratingly difficult. Students are required to complete over 30 credits of gen-eds, a large portion of which bears no direct relation to their chosen major. Among these requirements, 8 credits are allocated to Engagements. Requiring a math major to take “Engaging Aesthetics: The Art of Walking” or “Ethical Engagement: Are You a Stoic” is absolutely ridiculous. First-years’ time and money would be much better spent fulfilling the prerequisites for their major, exploring the prerequisites for other majors, or pursuing more extracurriculars.

By no means am I stating that philosophy and ethics classes should be eliminated; students who wish to study these subjects should be able to. However, the Engagements program relies on the false premise that mastering subjects such as history, physics, medicine, and business requires an understanding of the program’s four pillars. While the program hopes that students may discover newfound passions, this hope falls short when students are forced to enroll in classes they have no interest in. In such cases, the only “life skill” students develop is passing a class with as little effort and participation as possible. Unfortunately, I have experienced this pervasive apathy in all of my Engagements courses, when a teacher must resort to cold-calling because no one cares enough to contribute to the discussion. More flexibility for students pursuing a degree would ultimately serve both students and teachers better, creating a classroom environment where both parties are engaged. I do acknowledge that the Engagements program attempts to give students a sense of choice through their vast array of courses. I soon found out, though, that this was merely an illusion, considering the fact that every single Engagement class is essentially a philosophical inquiry. To those who think I am exaggerating, I urge you to read the descriptions of the classes online. I’m not lying.

The almost comical irony of Engagements is evident in the existence of the Echols Scholars Program, a selective track in which students are exempt from all gen-ed requirements, including Engagements. The purpose of Echols is to provide students with the opportunity to explore their diverse interests and enroll in advanced courses within their chosen fields from the outset of their time at UVA. If Engagements are truly considered crucial for “preparing [students] for life,” it raises a noteworthy question: why is it considered an honor to be recognized as an Echols Scholar, in which first-years’ primary advantage is their exemption from Engagements and gen-eds? This contradiction raises doubts about the perceived importance of these courses. I spoke to some Echols Scholars to hear their thoughts. Sadé Winston, a first-year biochemistry major, expressed, “I think engagements are a waste of time. The fact that [students] are forced to take those classes and pay the same tuition as me is crazy. It’s a ploy for money.” Another first-year computer science major shared, “Because I don’t have to take gen-eds or engagements, I’m ahead on integration electives and pre-reqs for the CS major. I could also double major in econ and still finish in 3 years. I don’t even have related AP credits to cover any pre-reqs, but I’ll still be able to graduate a year early because I didn’t have to waste any credits on useless classes.” I think they sum it up perfectly. Engagements are simply an impractical burden.

UVA must reevaluate the merit of Engagements and gen-eds for students. Is the university really creating well-rounded graduates? Or are they actually just preventing students from receiving an education tailored to their academic and financial needs?

- Mira Ramachandran

The idea behind the requirement is fine, but the implementation via a relatively short set of seminars is not. I did read the course descriptions, and they are full of the current liberal speak / DEI word salads and buzz words that infer these are simply justifications for “faculty” (How many tenured professors teach them? My bet, less that a handful, if any.) to fill the hours and check off their needed commitments to “name the needed topic” by the administration, and justifying the people who measure it. Net, if its important, it’s a full semester course, nothing less.